What significance does shape hold? A discussion on glucose monitoring devices and 3D registered trade marks.

Firstly, two declarations of interest.

- I’m a type 1 diabetic and a Freestyle Libre 2 Sense evangelist. My Libre Sense continuous glucose monitoring system (CGM) has transformed my ability to control my condition. It works using an on-body unit (OBU) which sits on my arm, inserting an electrochemical sensor under the skin to measure glucose levels in the interstitial fluid around the cells. Data from the OBU is transmitted to my ‘phone, which analyses and presents it to me to help me monitor and predict glucose level movement and trends. And it works very well. There are circa 6 million users of this tech worldwide.

- I’m also a trade mark lawyer who has on occasion argued in front of the UK Court of Appeal on issues concerning 3D registered trade marks. The validity of such marks is notoriously challenging to prove.

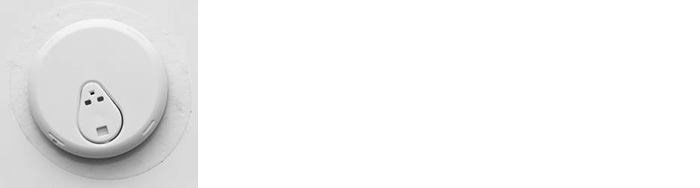

And so, I couldn’t let Abbott Diabetes Care v Sinocare Inc. and others pass by without comment. It was a case before the UK High Court about Abbott’s UK registered trade mark number 3779922 for sensor-based glucose monitors; CGMs in class 10. The representation of the mark is pictured below. Effectively it is Abbott’s OBU.

Abbott sued Sinocare for infringement of this 3D trade mark (on 10(2)(b) and 10(3) TMA 1994 grounds) and for passing off in respect of Sinocare’s CGM which was launched in the UK in January 2024, and which looks like this:

Sinocare denied infringement and counterclaimed for invalidity of the trade mark.

The case engaged the now fairly classic questions around enforceability of 3D marks, namely:

- in what circumstances do shape marks have the necessary distinctive character (section 3(1)(b) TMA)

- do surveys help with this question

- are the characteristics of the shape trade mark necessary to obtain a technical result and are therefore invalid (section 3(2)(b) TMA)

Abbott’s trade mark claim and passing off claim both failed and the registered trade mark was found to be invalid.

Distinctive character

If you are seeking to enforce a shape mark, you must be able to demonstrate it has distinctive character – i.e. that a significant proportion of the relevant consumers, seeing the mark used in relation to the relevant goods, would perceive it as designating the goods of a particular undertaking (and no other). It’s notoriously challenging to demonstrate this with a shape mark as opposed to a traditional word or figurative mark, since consumers are not in the habit of making assumptions about the origin of products on the basis of their shape alone, in the absence of any graphic or word element.

And back in 2002 in Nestle SA v Unilever Plc [2002] EWHC 2709 (Ch) (18 December 2002), the “sleight of hand” with shape marks was well articulated by Jacob J (as he then was). Effectively a product shape can become well known because it is advertised heavily with corresponding word trade marks, such that the consumer then starts to recognise the shape as coming from the owner of those trade marks. The shape then itself gets registered a trade mark and is then sought to be enforced against other manufacturers who use the same shape to sell products under their word trade marks. As Jacob J put it: “no one is deceived or misled. I do not think that is what the European Trade Mark system is for”.

Shape mark owners tend to seek to meet the test using evidence of acquired distinctiveness – the education process that the relevant consumers have been through. Here, Abbott did no different. The court looked at a significant amount of factual evidence setting out Abbott’s various marketing campaigns, product guidelines, packaging, app screenshots. But it could not find evidence that the circular shape of the OBU “means Abbott” to the relevant consumer. It found that the Abbott traditional trade marks (word and figurative) carried the burden of badge of origin, whereas the shape focussed on the functional aspects of the product. The 3D mark lacked distinctive character and was therefore invalid.

Did surveys help Abbott?

In short: no. Abbott relied on two surveys conducted in 2022 but they did not comply with the all of the Whitford Guidelines which govern the conduct of surveys. For those contemplating adducing survey evidence, the judgment is a useful walk through the various attacks that are levied on evidence of this nature. Abbott was certainly not helped by the fact that it did not bring a survey expert to court to testify to the evidence, even though Sinocare had challenged the probative value of the surveys, but that might not have made any difference to the result. The court found that the surveys at most demonstrated recognition of the shape trade mark – but crucially not that the shape indicated origin.

Shape or characteristics necessary to obtain a technical result

Sinocare also argued that the trade mark was invalid because it consisted exclusively of the shape or another characteristic of goods necessary to obtain a technical result. Of the 6 features identified below, there was a dispute between the parties as to what the essential characteristics of the product were:

The court agreed with Sinocare that the essential characteristics were features 1,3,4 and 6. Reviewing the CJEU caselaw in Lego , Philips and Lindt , the court also agreed that, given that each of these four features performed a technical function (notwithstanding that the technical results of some of the features could be achieved by other means), the 3D trade mark consisted exclusively of a shape of the goods which is necessary to obtain a technical result. And so the registered mark was found to be invalid under this ground too.

Non-Infringement

Having found the 3D trade mark invalid on two grounds, the question of whether there had been infringement was not strictly required to be answered. The court did find though that there was no likelihood of confusion required by section (10)(2)(b) TMA and that Abbott had also not made out its case under section 10(3) TMA. Unsurprisingly in the circumstances, the passing off claim also failed.

What’s the prognosis for shape marks?

They’re not dodos, but proprietors need to educate consumers effectively in order to build an IP asset worth enforcing. Before launch of the relevant product, it is key to consider what function the shape is going to play in terms of the origin of the product. There is little point in advertising the shape alongside extensive use of the word or figurative marks, as the shape will likely not be an indicator of origin. And there lies the dichotomy. How do you educate the consumers on origin purely through the shape? Of course, the consumers don’t necessarily need to know the actual name of the originator of the products protected by the shape mark – to know, because of the shape, that there is a single origin is sufficient. But it takes brave marketing to omit reference by name to the undertaking which is responsible for the product.

As to technical function, the introduction of capricious but essential elements of the shape which achieve no technical result will assist in navigating through section 3(2)(b) TMA.

And whatever you do, be very careful before adducing survey evidence. It tends not to help you.

Must go – my phone has beeped to tell me that my glucose levels have dipped. Time for some cake, a slice of Viennetta, or perhaps a KitKat.

Contact

Mark Daniels

Partner

mark.daniels@brownejacobson.com

+44 (0)121 237 3993