Rights to use sporting and recreational facilities are capable of taking effect as an easement.

Facts

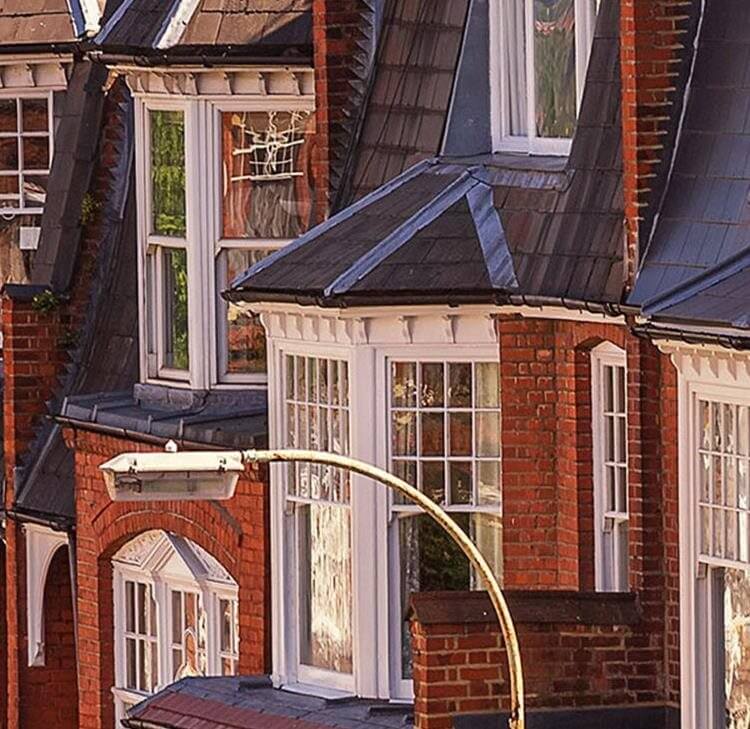

RVTL was the freehold owner of a timeshare complex (the Dominant Land) and held the land on trust for (ultimately) the timeshare owners. The Dominant Land had been transferred to RVTL’s predecessors in title in 1981 (the 1981 Transfer). The 1981 Transfer granted a right:

'..for the Transferee its successors in title its lessees and the occupiers from time to time of the property to use the swimming pool, golf course, squash courts, tennis courts, the ground and basement floor of Broome Park Mansion House, gardens and any other sporting or recreational facilities (hereafter called "the facilities") on the Transferor's adjoining estate.'

The land retained by the Transferor in the 1981 Transfer (the Servient Land) was now owned by DREL.

RVTL claimed that the Dominant Land had the benefit of an easement to the free use of all sporting and recreational facilities from time to time provided within the Servient Land. These currently included gardens, tennis courts, squash courts, a putting green, a croquet lawn, an 18-hole golf course, some indoor facilities (e.g. a billiard room and a sauna) and an indoor swimming pool built in 2005 (which replaced the original outdoor pool). DREL on the other hand claimed that the rights granted by the 1981 Transfer were not capable of amounting to an easement but were simply personal rights existing between the original parties to the 1981 Transfer (so DREL was now entitled to charge for use of the current facilities).

Issues

-

Did the rights granted by the 1981 Transfer accommodate the Dominant Land?

-

Were those rights capable of forming the subject-matter of a grant (i.e. not expressed in language which is too wide and vague, not involve any expenditure by the owner of the Servient Land and not deprive the owner of the Servient Land of control or possession of that land)?

Decision

- The rights benefited the Dominant Land itself, as well as benefiting the timeshare owners as individuals. Where the actual or intended use of land that benefits from a right granted is itself recreational (as will generally be the case for holiday timeshare developments like this one), the requirement for a right to accommodate that land will generally be satisfied.

- The Supreme Court considered two elements separately – whether the rights deprived the owner of the Servient Land of control or possession of that land (known as ‘ouster’) and whether the rights imposed upon the owner of the Servient Land obligations to spend money or do anything beyond mere passivity (known as ‘passivity’).

There was no ouster simply because the timeshare owners could step in if the owner of the facilities stopped managing and maintaining them. It was wrong to test whether a grant of rights amounted to an ouster by reference to what a dominant owner could do by way of step-in rights. Ouster should be determined by the expectations of the parties at the time of the grant. Here it was expected that the owner of the Servient Land would maintain the facilities. In addition, step-in rights were rights to reasonable access for maintenance. Provided that the facilities could be used by the timeshare owners without taking control of the Servient Land, then there was no ouster.

In relation to passivity, the owner of the Servient Land had undertaken no obligation to maintain the facilities (even if the parties shared an expectation that it would do so). The rights extended only to such recreational facilities as existed on the Servient Land from time to time and some meaningful use could be enjoyed even if the owner of the Servient Land failed to maintain them (e.g. the timeshare owners could fill the pool or mow the lawns).

Points to note/consider

This case will cause land law textbooks to be rewritten as it is the first time that an easement to use a wide range of sporting and recreational facilities in a leisure complex has been recognised by a court in this country. The case shows that the categories of easements are not closed and can adapt to meet the changing needs of society as long as the basic characteristics of an easement are satisfied (famously set out by the Court of Appeal in Re Ellenborough Park [1956] Ch 131). These are:

- there must be a dominant and a servient land;

- the right must accommodate the dominant land;

- the dominant and servient lands must be owned or occupied by different people;

- the right must be capable of forming the subject-matter of a grant (see above).

In this case, the Supreme Court took the view that sporting and recreational activity is so clearly a beneficial part of modern life that the law should support structures that promote it, rather than treating them as devoid of practical utility or benefit.

The Court of Appeal had looked at each right individually and had determined that the rights over the outdoor facilities could amount to an easement but that there was no easement in relation to the indoor facilities or the indoor pool (which was not in existence at the time of the 1981 Transfer). However, the Supreme Court decided that this approach was incorrect and agreed with the original High Court decision that the grant of rights should be treated as a bundle that would stand or fall together. On that basis, the easement extended to the indoor facilities (even though the easement was exercised over, or with the use of, chattels or fixtures on the Servient Land) and to the indoor pool which formed part of the communal parts over which the timeshare owners already enjoyed rights.

Lord Carnwath gave a strong dissenting judgement in the case. He disagreed on the passivity issue, arguing that the enjoyment of the rights (particularly the golf course and the swimming pool) could not be achieved without the active participation of the owner of those facilities in their provision, maintenance and management. He also did not believe that either principle or authority supported the rights claimed taking effect as an easement (describing them as more akin to permanent membership of a country club than a property interest).

Contact

David Harris

Professional Development Lawyer

david.harris@brownejacobson.com

+44 (0)115 934 2019