While the primary objective of an inquest is to determine the cause of death, a coroner must also assess whether the evidence reveals ongoing concerning circumstances that could pose a risk of future fatalities. When such risks are identified, the coroner is obligated to issue a report known as a Prevention of Future Deaths (PFD) report, also referred to as a Regulation 28 report.

In a healthcare context, PFD reports serve as a crucial mechanism for enhancing public health, welfare, and safety. Healthcare providers and commissioners can derive valuable insights and improvements not only from PFD reports directly addressed to them but also from those addressed to other similar organisations.

With that in mind, we have reviewed 40 PFD reports related to mental health deaths, published over a 6-month period between September 2024 and February 2025. The recurring themes and issues identified can help mental health care providers to:

- implement preventive measures and continuous improvements, and

- be aware of issues likely to be explored at inquest, thereby ensuring sufficient preparation in advance of the hearing.

We have also provided insights on what providers should consider when preparing organisational learning evidence for the coroner.

Summary

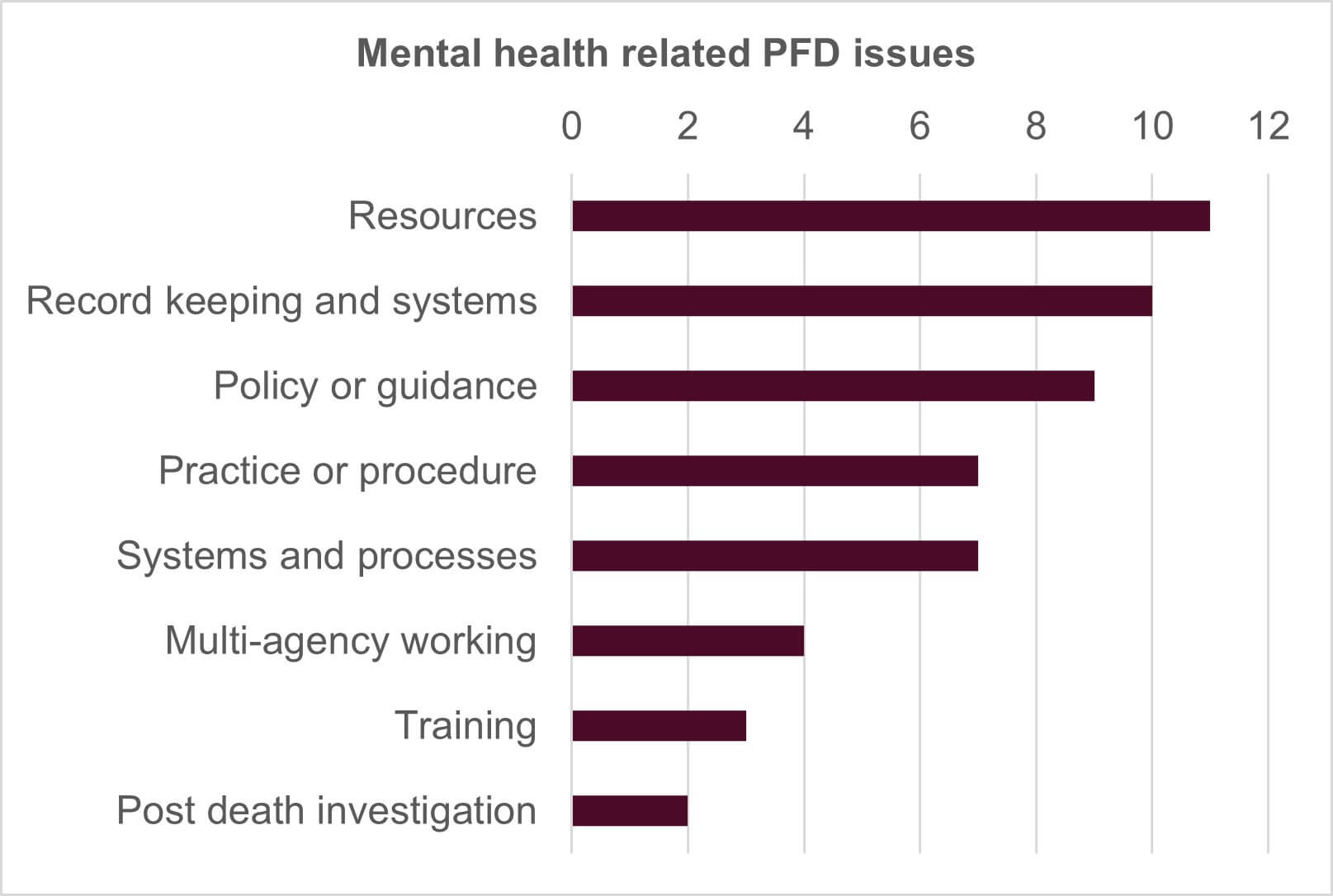

A PFD report can refer to multiple issues or risks that have arisen out of one inquest, whether connected to the cause of death or not. We identified 53 key issues arising from the 40 PFD reports we looked at. We considered that those 53 issues could be broken down into eight main themes or categories:

- Resources

- Record keeping and systems

- Policy or guidance

- Practice or procedure

- Systems and processes

- Multi-agency working

- Training

- Post death investigation

The chart below summarises how frequently each issue arose:

Resources

Perhaps not surprisingly, the issue of resources was raised most frequently in eleven PFD reports.

The most common resource concern was regarding bed shortages, mentioned in four PFD reports. The lack of inpatient psychiatric beds was noted in Suffolk, Norfolk and West Sussex, Brighton & Hove, and more broadly throughout England and Wales.

Bed shortages can result in lengthy, “unacceptable” waits in A&E, with one patient waiting for 26 days for an inpatient psychiatric bed which never materialised. Two inquests highlighted that A&E is an unsuitable setting to “hold” people in need of a mental health bed, especially for individuals with autism or who are neurodiverse, as the environment can worsen their mental health. The national shortage of suitable beds for autistic people and for those who are transgender was also identified as a concern.

The delay in obtaining s.135 Mental Health Act (MHA) warrants in London was identified as an issue. A s.135 warrant, issued by a magistrate in the county court, authorises a police officer to enter premises and remove a mentally disordered person to a place of safety. However, it was noted in two PFDs that Westminster and Uxbridge Magistrates Courts handle s.135 warrant applications from all 32 London boroughs, and there are a limited number of video hearing slots. Applicants may have to wait several days for a hearing and there is no official fast track procedure. Consequently, there is an ongoing risk that individuals will harm themselves or others during the time taken for a warrant to be granted and executed. These PFDs were addressed to the Ministry of Justice and the Commissioner of the Metropolitan Police.

In another inquest, concerns were raised regarding crisis telephone numbers for individuals feeling suicidal. These numbers were not being answered, and the service was not catered for those with hearing difficulties or other disabilities. Further, it was noted that crisis telephone numbers might not be user-friendly for younger individuals, who are generally more accustomed to using apps and social media to communicate, rather than traditional phone calls.

The risks associated with the nationwide high demand for adult ADHD services and lengthy waiting lists was highlighted in one inquest. The Area Coroner noted:

“It is of concern that patients who have been identified specifically of being at risk as a result of undiagnosed and/or untreated ADHD…remain on significantly lengthy waiting lists during which time they are not receiving treatment, their condition is not monitored and there is a risk…that their condition may deterioration or lead to risk or harmful behaviour and death.”

The widespread shortage of suitable placements for individuals with complex needs, such as autistic spectrum disorder, ADHD and learning disability, both in the community and the NHS was noted in a separate inquest.

Concerns were also expressed about the limited sources of qualified mental health support for police officers when responding to those suffering a mental health crisis in the community.

Insight

Coroners understand that individual healthcare providers often cannot address resource shortages alone. Therefore, most PFD reports on these issues are directed to NHS England and the Department of Health and Social Care (and sometimes Integrated Care Boards). It is vital for healthcare organisations to demonstrate at an inquest the work they have done or are doing towards maximising the resources they have, and to evidence where further potential work falls out of their control.

The potential unsuitability of crisis telephone lines for young people, who are generally more accustomed to apps and social media, is interesting. No response to this PFD is available yet, however we are aware that the NHS already recommends certain apps for mental health care. If providers would like any further guidance in this area, please do get in touch with us.

Record keeping and systems

Record keeping and systems arose in ten PFDs. A common concern, cited by four coroners, was regarding staff not having access to all of the individual’s medical records. Examples included:

- A&E staff not having access to mental health records.

- The talking therapies team not having access to the community mental health team’s notes, and vice versa, despite both teams coming under the same Trust.

- Bank staff in the psychiatric liaison team not being allowed access to the electronic computer system.

- Hospital trusts being unable to access each other’s notes due to the use of different computer systems.

In all cases, the concern was that vital information wasn’t being shared with everyone involved in the individual’s care, thereby posing fatal risks. Some PFDs were addressed to NHS England, as it was recognised that moving to a combined electronic records system is a national issue involving NHS leadership.

Other record keeping issues included:

- Incomplete or absent risk assessments. In one inquest, no written risk assessment was recorded by a community mental health team for seven months, leading to inadequate information sharing and hindering investigations into the death.

- An apparent lack of minimum standards for note keeping for accredited psychotherapists – this PFD issue was addressed to the British Association for Counselling and Psychotherapy.

- No notes being made by a practitioner who declined a patient referral, meaning their identity and reasons for declining the referral were unknown.

- The Summary Care Record not including a section where care plans could be uploaded, posing patient safety risks due to inaccessible care plans.

Insight

Record keeping is a persistent issue in both patient safety investigations and inquests. In a mental health context, deficiencies are often found with risk assessments, care plans, handovers, documenting patient observations and s.17 leave reviews. Regular audits to identify and address gaps in record keeping, along with staff training on the importance of accurate patient notes, are some of the ways providers can assure coroners that improvements are being made. Whilst transitioning to an integrated records system may be beyond the control of individual providers, organisations must still demonstrate their efforts to ensure staff have access to the necessary records. Working collaboratively with neighbouring Trusts or partner agencies and ensuring access to health records for bank and temporary staff are some recommended strategies.

Policy or guidance

At a national level, the lack of guidance on cross-titration of medication was noted. Although cross-titration is commonplace in psychiatric care, the absence of national guidelines results in the process being largely determined by each prescriber’s individual practice. Additionally, the evidence indicated that creating local guidance was challenging due to the range of settings in which cross-titration may occur, the complexity of prescribed medications and limited evidence regarding how it should be undertaken. The coroner expressed concern that the process “appears to be undertaken on the basis of limited consensus, and variation in care could lead to future deaths.” This PFD was addressed to the Royal College of Psychiatrists.

Another inquest identified the absence of a formal framework, either locally or nationally, to facilitate inter-specialty communication in mental health care, particularly in complex and dynamic cases. This PFD was addressed to NHS England to consider.

A separate inquest considered NHS England’s smoke-free policy. Whilst clearly aimed at protecting life and promoting health, the coroner noted the policy may not suit mental health wards and could potentially increase patients' risk of self-harm and suicide. In the case, patients were prohibited from smoking on hospital grounds but also could not leave the grounds during short "grounds" leave. This forced patients to smoke by the road at the edge of the grounds, in a poorly supervised area, resulting in the patient slipping away unnoticed and ultimately taking her own life. The PFD was addressed to various national bodies, including NHS England.

At a local level, the following policy or guidance issues were identified:

- An absence of guidance for health board staff on managing individuals with both addiction and mental health issues, and on collaborating with third sector agencies who provide the addiction services.

- A lack of policy or guidance regarding risk assessing fixtures and fittings supplied by the Trust. Consequently, there was a risk that these items could be used by patients with acute mental health conditions to harm themselves or take their own life.

- NICE guidance NG225 on self-harm, which requires a comprehensive mental health and social needs assessments for all individuals who have self-harmed, not being followed when the individual attended hospital reporting an overdose.

- A lack of guidance for frontline Metropolitan police officers on using their s.136 MHA powers for individuals who are likely to be missing but not yet reported as such.

Insight

In instances where there is an absence of, or issues with, national policy, healthcare providers should bring this to the attention of the coroner. However, providers must evaluate whether a local policy can be instituted temporarily until the issue is addressed at a national level and demonstrate efforts to implement an interim solution. Liaising with neighbouring Trusts or similar organisations to determine if they have effectively implemented policies or guidance to address the identified gap could prove beneficial.

Healthcare organisations should conduct regular reviews of their own policies and guidance documents. This is to ensure a comprehensive set of policies addressing all necessary areas, and that they remain up to date. The review should include references to national and international guidelines and policies, which evolve frequently. Providers should also implement appropriate mechanisms to ensure that staff adhere to both local and national guidelines and policies.

Practice or procedure

Issues with individual practice or procedure arose in seven inquests. Concerns were expressed about risk assessments in three inquests. In one case the patient’s high risk of suicide had been underestimated, and in the other a holistic assessment of self-harm had not been undertaken, contrary to NICE guidelines.

Concerns about treatment were raised in two inquests. In one, the coroner highlighted the insufficient steps taken by the healthcare provider to address a detained patient’s refusal to accept necessary and appropriate medical treatment over several years. A lack of efforts to persuade the patient to accept the treatment and inadequate consideration of available powers under the Mental Capacity Act and s.63 MHA were noted.

In another, concerns were raised about using Olanzapine depot injections for psychiatric in-patients who have a history of refusing vital sign checks. There is a small albeit real risk of death from these injections, which can largely be eradicated by regular vital sign checks. Unless a dedicated member of staff is assigned to complete these checks, they can easily be missed due to other work demands and distractions.

Insight

Although it did not emerge in any of the PFDs we reviewed, we frequently see concerns being raised at inquests around the insufficient involvement of families and carers in an individual’s care, and the failure to act upon concerns raised by the family. It is essential for providers to demonstrate at the inquest what systems are in place or what improvements have been made to promote the “triangle of care”.

Systems and processes

Issues with systems and processes arose in seven inquests. Examples included:

- An NHS Trust conducting risk assessment audits for patients accepted into the community mental health team, but not for those whose referrals were declined and who received no ongoing mental health care.

- The system for prescribing mental health medication to individuals in crisis was confusing, and it was not clear whether NHS 111, the Out of Hours GP service, an individual’s own GP or their mental health team was the decision maker regarding prescriptions.

- There being no robust or reliable system to ensure that a First Response Team dealt with its case load efficiently and effectively, followed up on referrals and responded to queries from other services or clinicians.

- The system of granting s.17 leave for patients was insufficiently robust, with concern that conditions of leave might not always be thoroughly reviewed.

- High-level intermittent observations not being carried out efficiently, with the system failing to prevent the individual from taking her own life on an inpatient ward.

Insight

Providers must identify whether systemic issues contributed to a patient’s death. They need to distinguish between not following an existing system or process, and the absence of one altogether. Reviewing past incidents to see if the issue has occurred previously (and therefore whether this is a recurrent issue) can help determine this.

If a system is in place but it wasn’t followed, providers should consider what steps are required to prevent reoccurrence, which will require exploration of the barriers to compliance. For example, training issues, cultural issues, resource issues etc. Different barriers will require different resolutions; without understanding why there has been a lack of compliance, it is difficult to ensure the solution is appropriately targeted. Organisations should also think about whether the issue could arise in similar teams or services across the Trust, and if the improvement action needs wider implementation. When introducing new or improved systems post incident, ensure they are properly rolled out, that staff (particularly those giving evidence) are aware and necessary training is provided.

Multi-agency working, training and post-death investigation

These issues occurred less frequently in the PFDs we reviewed. Examples included:

- Various specialties involved in the care of a patient, who had mental health issues due to suffering from chronic prostatitis and persistent pain, failing to liaise and communicate with each other, leading to a lack of understanding of each specialty’s plans and actions.

- A lack of communication between the individual’s college and the child and adolescent mental health services (CAMHS), leading to the college being unaware of the individual’s current mental health condition and the fact that he had withdrawn from CAMHS support.

- No formal, effective training for clinicians regarding the Dual Diagnosis pathway, including what it does and does not provide, how to access it and its benefits.

- Issues identified in the post-death investigation not being resolved nearly two years after the death, raising concerns about the timeliness of addressing patient safety risks.

- A Trust making limited contact with a bereaved family after the patient’s death, and providing no information about the care given to the individual. The family had no opportunity to raise issues or participate in any significant way in the patient safety investigation.

- Insufficient information sharing between investigating police officers, the Criminal Justice Liaison and Diversion service and the custody serjeant about the individual’s mental health, risk, suicide history, previous engagement with mental health services and family concerns.

Insight

Whilst issues with post-death investigations arose in only two of the PFDs reviewed, we have seen this issue arise frequently in other inquests. Common issues include a lack of meaningful communication with bereaved families following an individual’s death, not involving families and crucial staff members in patient safety investigations and failing to identify key learning opportunities. We always encourage healthcare providers to ensure bereaved families and key personnel are appropriately engaged and involved in post-death investigations and reviews, in accordance with the Patient Safety Incident Response Framework (PSIRF) guidance.

Summary

This analysis has highlighted several key themes within mental health care. The insights gained from these PFD reports provide a valuable opportunity for continuous learning and improvement, ultimately contributing to better healthcare outcomes and patient safety.

The new 10-year NHS Plan is set to be published in the spring, and we are interested to see the specific plans regarding mental health care, particularly given this is a priority area for the government. We are also keen to understand how the government plans to make better use of technology, as moving from analogue to digital and embracing digital transformation has been touted as one of the three “key shifts”. It is hoped that the plan will address some of the current challenges faced by both patients and providers and help pave the way for a more robust and responsive mental health care system.

Katie Viggers

Professional Development Lawyer

katie.viggers@brownejacobson.com

+44 (0)330 045 2157