Unlawful delegation of decision-making powers

On 16 December 2022 the Planning Court handed down a judgment in relation to a statutory review under Section 288 of the Town and Country Planning Act 1990 (TCPA 1990) that could have wider implications for the delegation of decision-making powers by public bodies.

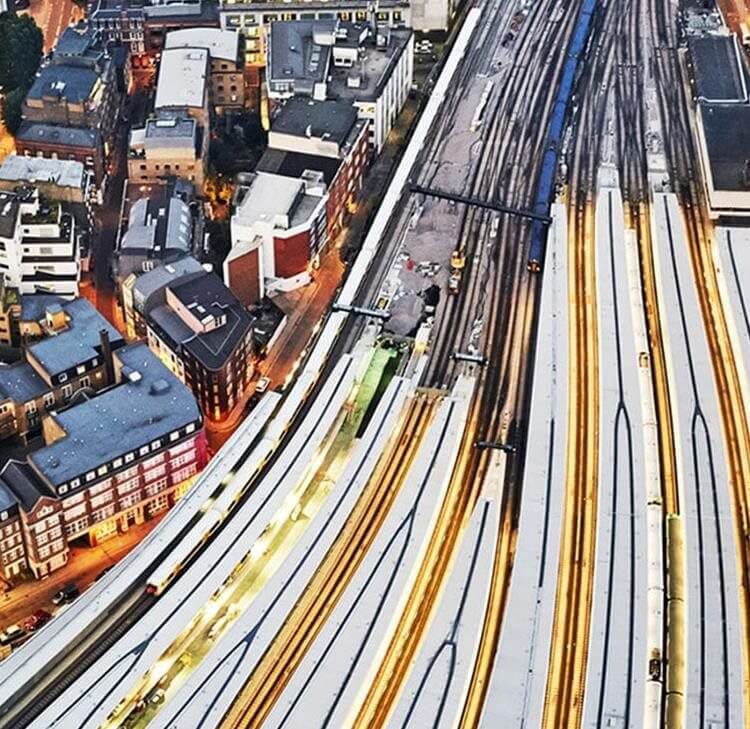

The appeal, (Smith v Secretary of State for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities & Anor [2022] EWHC 3209 (Admin)), concerned a decision by the Planning Inspectorate (PINS) to dismiss an appeal by the claimant against the refusal by the local planning authority, Hackney Borough Council, of an application for advertisement consent for a large advertising billboard. In reaching the decision the Planning Inspector responsible had enlisted the help of a lower ranking ‘Appeal Planning Officer’ or APO caseworker, and the S.288 application concerned whether this had been done lawfully.

The applicable legal framework, which was not in dispute, required that the planning appeal had to be determined by the appointed inspector (on behalf of the Secretary of State): they were not entitled to delegate their decision-making functions. The main issue is whether the inspector unlawfully sub-delegated his functions to an inexperienced junior officer, whose recommendation and reasoning he adopted without alteration; and whether that was an unfair process.

The Planning Court noted that a recent shortage of planning inspectors had led to a practice of recruiting lower ranking staff to help inspectors by undertaking site visits and helping to draft decision letters. This took place under an initial pilot scheme in 2013-14 and was subsequently rolled out more widely. APOs now act as caseworkers doing preparatory document work for a decision, conducting site visits and producing draft decisions.

In this case a PINS inspector, and an unqualified APO were assigned to the appeal. At the inspector’s request the APO carried out a site visit and provided a detailed reasoned written recommendation and decision template for the responsible inspector. The report included judgements on the main planning issue, the impact on the amenity, and on the weight to be given to these impacts when reaching a conclusion on the merits of the appeal proposals. The APO’s recommendation was to dismiss the appeal, and the inspector accepted this together with the report’s reasoning in full. The inspector “topped and tailed” the decision without adding any further reasoning, signed it electronically, and sent it to the claimant.

Role creep

The Planning Court Judge held that there could be no possible objection to the use of APOs to assist with assembling facts and evidence, document handling and carrying out site visits representing the inspector. However, in this case the APO were required to exercise a professional planning judgment which they were not professionally equipped to exercise. Mr Justice Kerr found that this was an unlawful delegation of power from the Inspector to the APO which rendered the process unfair to the claimant. The initial planning judgment being made by the junior and inexperienced APO provided the inspector with a powerful steer, such that the inspector failed to determine the appeal independently of the APO.

The immediate result was that the Planning Court quashed the inspector’s decision, which will now need to be redetermined by a different inspector, but the decision potentially has wider implications.

Delegating within the law

The legal judgement that over-reliance on APOs could render a decision unlawful may have significant implications for previous appeal decisions decided by PINS. However, the number of such decisions is likely to be relatively small, given the statutory time limit of six weeks for challenges under Section 288 TCPA 1990.

Perhaps the more serious impact may be that PINS will have to somewhat shrink the role of APOs in the future, as they will face increased scrutiny of their involvement in decisions. This could well have implications for its ability to deal with high case numbers in a timely fashion over the coming months, the very purpose APOs were intended to serve.

The Planning Court decision should also serve to remind public bodies of the need to comply with legal limits on the delegation of decision-making powers.

Justice Kerr distinguished the use of unqualified APOs in appeals from situations where local planning authority officers write reports advising decision takers on how applications should be determined. The judgement mentions determinations by planning committees, and where a portfolio holder exercise delegated powers, emphasising that these present a different factual and legal context. That is likely to be the case where the case officer writing the report is a qualified and experienced professional, albeit they may less senior and not have been given delegated powers.

However, local planning authorities may wish to review their processes and procedures where senior officers exercise delegated powers to grant or refuse planning permission based on a report written by the most junior inexperienced officers who may not yet have obtained a relevant planning qualification or professional membership. In those cases, it may be prudent to:

- ensure those junior officers clearly separate any judgements and recommendations from the factual elements of the delegated report; and

- provide an account of how the determining officer has arrived at their own relevant judgements and conclusions based on the facts of the case, as well as reflections on the findings of the case officer.

With public sector bodies generally facing reduced resources and, like PINS, trying to deploy innovative ways to “do more with less”, recruiting less experienced and unqualified juniors to assist over-worked decision-makers is an obvious way to achieve efficiencies.

Such an approach can also help nurture future talent in-house, indeed the introduction of APOs to PINS was also intended to provide a route for development to inspector to aid longer-term succession planning.

At all times, public bodies should keep in mind the legal context of their decision-making powers and ensure that they exercise administrative powers in a way that is fair in all the circumstances.

Failure to do so in relation to one decision can render that decision unlawful. Where the unfairness is due to a systematically unlawful approach to decision-making the result is that all decisions taken through this approach may be at risk of challenge.

Contact

Alistair Taylor

Associate

Alistair.Taylor@brownejacobson.com

+44 (0)330 045 2970